What do Warwick students think about the 2022 UCU strikes?

An investigation by Zac Attewell

For three days during November 2022, the University and College Union (UCU) called for industrial action at universities across the country – including Warwick. On Thursday 24, Friday 25, and Wednesday 30 November, university staff members took to the bus interchange to picket, erecting bright pink gazebos. Most of the protests consisted of holding placards, chanting, and playing music. Although other sessions included ‘teach-outs’ (discussing topics such as “What is the neoliberal university?”), poetry readings about the cost-of-living crisis, and an address by local Coventry MP, Zarah Sultana.

The national strikes were the first by an education union since 2016 when a legal threshold of 50% turnout was introduced to call for industrial action. UCU members voted overwhelmingly to strike with 84.9% of a turnout of 60.2% picking ‘yes’ over cuts to pensions. The strikes were the biggest of their kind in history, representing 70,000 staff across 150 universities, potentially impacting two and a half million students.

The aim of this article is to investigate why the strikes happened, how they affected Warwick students, and what students believe about the strikes and protests.

As part of our investigation, we surveyed Warwick students and whilst we cannot claim that the results are necessarily representative of the beliefs of Warwick students as a whole, we can say that students’ responses have helped illuminate the variety of ways that students have been impacted by the strikes and protests, as well as providing a plurality of opinions that students have on the issue.

Image: Warwick UCU

Image: Warwick UCU

Despite (according to a Warwick spokesperson) only one in seven Warwick staff members being UCU members and many unable to strike due to financial limitations, 85.7% of students who responded stated that they were affected by the strikes in some way. This is because students interact with a number of tutors on any given day. Many mentioned that they had lectures, seminars or advice and feedback sessions cancelled or postponed. In some cases, marks and feedback for assessments due to be returned were delayed.

"At least let us know whether our 9 a.m. is cancelled so we don’t trek all the way to campus for nothing"

One student reported: “Some lectures and seminars moved online; some continued as normal. Didn’t want to miss out so had to cross the picket line, which was stressful as an autistic student.” This was – at least in part – the goal of the protests. Students and staff not participating in the strikes had to ‘cross the picket line’ to get to their classes, an action seen symbolically as not supporting the strikes. Along with calls to skip class on strike days, those who otherwise support the striking staff are therefore forced to make the choice between missing out on contact hours or feeling guilty about making the journey through the crowd of protesters in order to attend class, which can be particularly distressing for some students.

Additional confusion arose from students not knowing whether or not their lecturer or seminar tutor would be participating in the strikes until the evening before or the morning of when their classes were supposed to be held. While many chose to inform their students well beforehand, UCU members are under no obligation to declare their intention to participate in industrial action in advance and are even encouraged not to by the union in order to provide greater pressure on university management. This can make it difficult for students to plan their schedules in advance, or as one respondent protested: “at least [let] us know whether our 9 a.m. is cancelled so we don’t trek all the way to campus for nothing”.

Image: Alarichall / Wikimedia Commons

Image: Alarichall / Wikimedia Commons

Image: Nick Efford / Flickr

Image: Nick Efford / Flickr

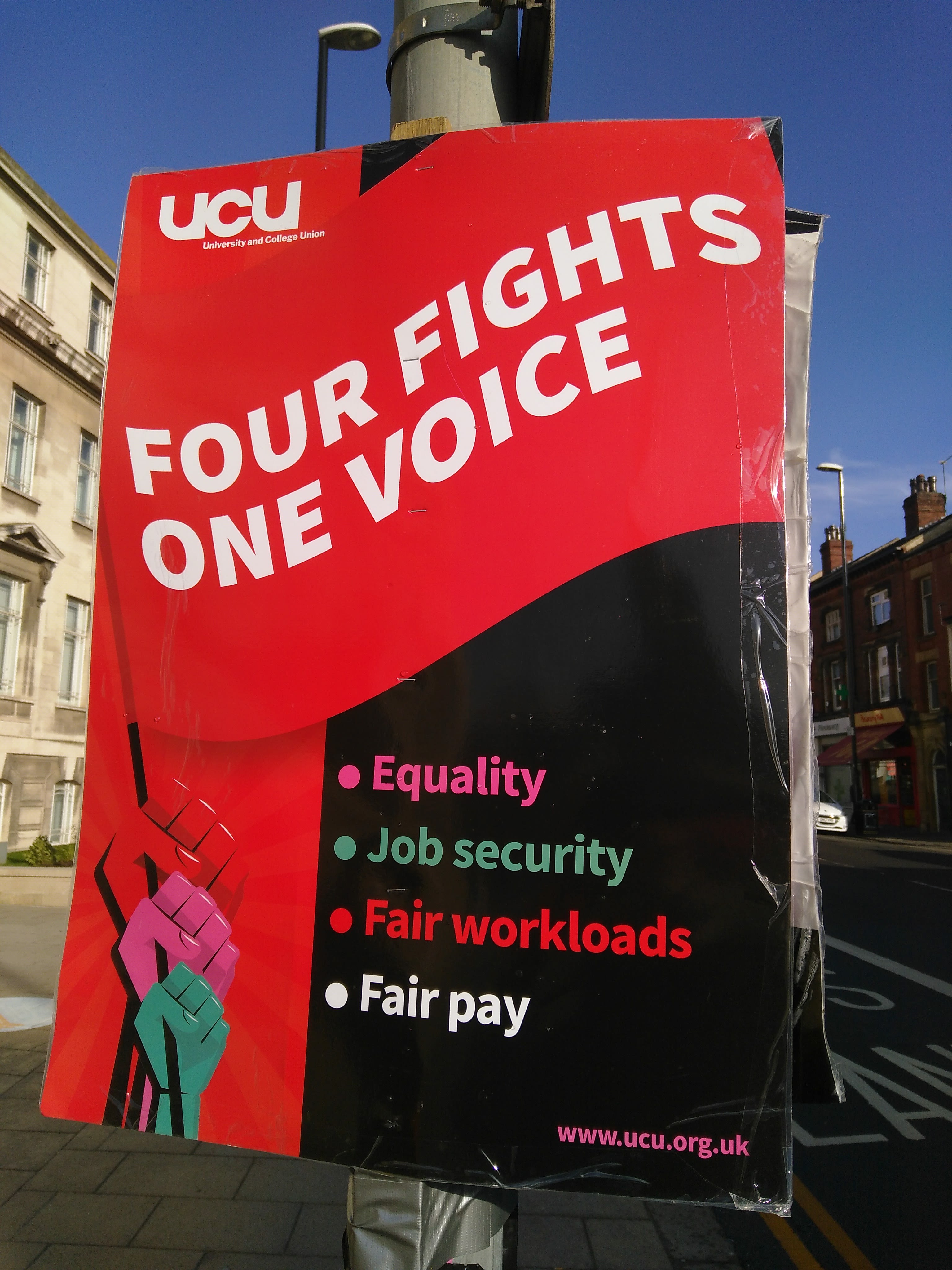

So, why did Warwick staff go on strike? UCU members voted affirmatively on two issues: pay and working conditions, and cuts to pensions. Warwick UCU released a list of demands, which we shall now discuss.

The most prominent of these demands is to reverse the package of cuts on the Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS), which is the pension scheme for academic staff at many UK universities. The UCU claims that the average union member will lose 35% from their guaranteed retirement income. They claim that these cuts were implemented due to a faulty valuation of the scheme in March 2020 at the start of the pandemic, at which time the scheme recorded a deficit of £14.1 billion. However, recent USS data shows that the scheme has not only recovered but is in a surplus of £1.8 billion. On top of this, the UCU is demanding future valuations be “evidence-based” and “modestly prudent”.

Another point of contention is pay. UCU demands an increase in salary at all points on the pay scale of at least inflation plus 2% or by 12%, whichever is greater. A new pay scale was implemented in August 2022, which increases salaries by 3% with up to 9% for those at the lowest spine points. However, the Universities and Colleges Employers Association claims that any further increase in salary will “put jobs at risk” since many universities already run a deficit. Despite this, the UCU asserts that this is “unacceptable” as average salaries have fallen behind inflation, resulting in a 35% real terms pay cut since 2009.

"They have had enough of falling pay, pension cuts and gig-economy working conditions - all whilst vice-chancellors enjoy lottery win salaries"

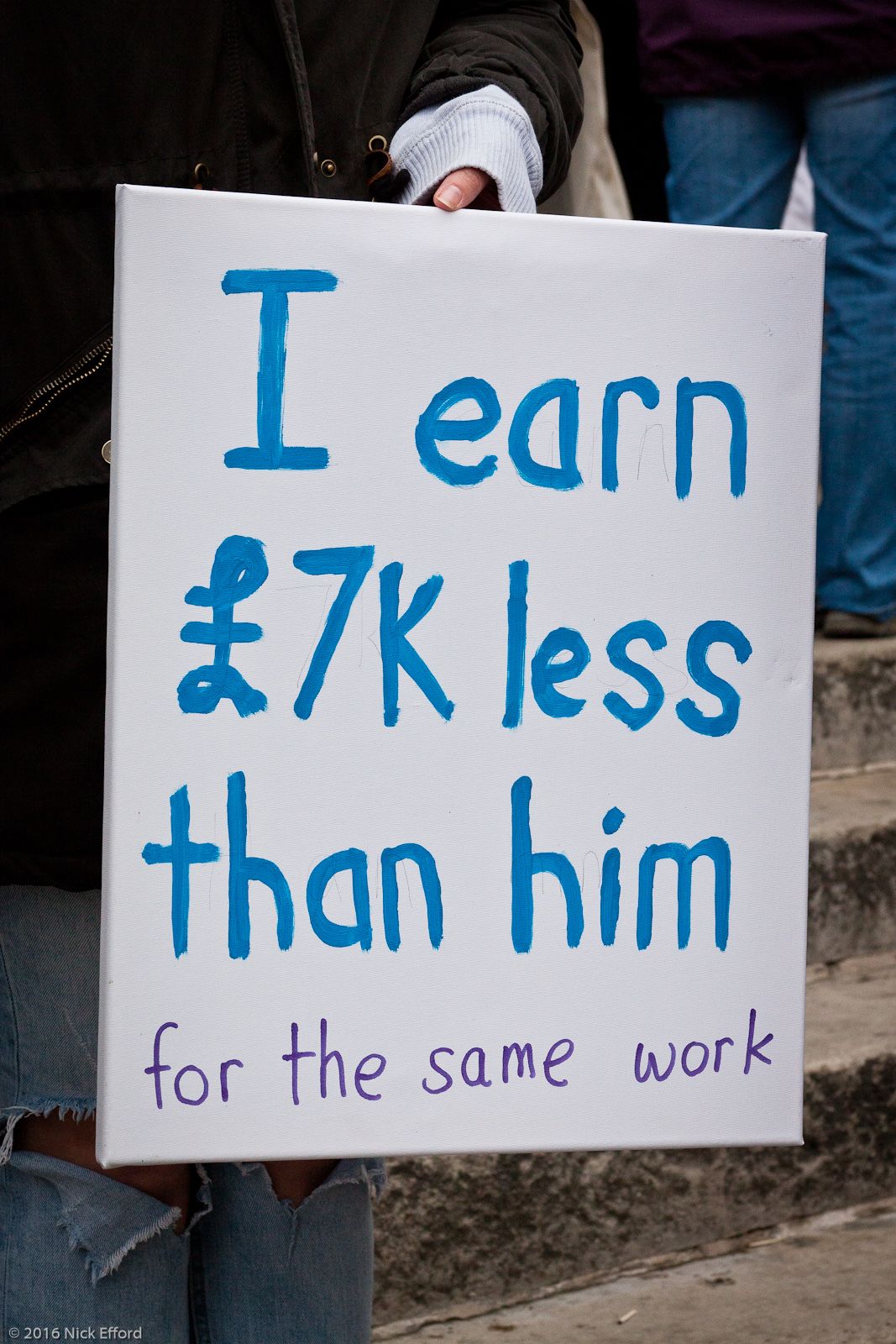

On top of this, the UCU calls for an intersectional approach to closing pay gaps due to gender, ethnicity, disability, and membership in the LGBTQUA+ community. Do these gaps exist at Warwick? A 2021 report by the university revealed that for the most part, men and women are paid the same for the same work, with an exception at the highest pay grade, where men earn significantly higher on average. Despite this, there does exist a gender pay gap at Warwick with men being paid on average 21.9% more than women. This is due to there being a greater proportion of men in higher-paying roles. Similarly, the report found a mean pay gap of 12.5% between white and ethnic minority staff, as well as an 18.4% disability pay gap and that self-declared LGBTQUA+ staff were paid on average 3.6% less. The report discusses the variety of factors attributed to these discrepancies and also notes that pay gaps are gradually decreasing year over year.

Another issue that Warwick UCU is protesting is the over-reliance of universities on casual labour. According to the UCU, one in three academic staff members is on a temporary contract. Additionally, the UCU claims the average university staff member works a full two days per week unpaid. This is partly because of an increase in administrative work, which has increased by 83% in the past three years, but also an increased requirement to use greater technology, particularly due to Covid and the introduction of remote learning.

UCU General Secretary Jo Grady summarised: “University staff are taking the biggest strike action in the history of higher education. They have had enough of falling pay, pension cuts and gig-economy working conditions - all whilst vice-chancellors enjoy lottery win salaries and live it up in their grace and favour mansions.” To fact-check this, according to Warwick’s Annual Report of the Remuneration Committee 2020, vice-chancellor Stuart Croft’s salary was £308,502 for the 2019/20 year - or 6.2 times the median salary of academic staff at Warwick. This represented a real terms pay rise since he started his position 2016.

So, what do Warwick students think of the strikes?

Our survey found that while only a small proportion of respondents (28.6%) took part in either the classes boycott or actively picketed, the vast majority (89.5%) stated that they supported the strikers’ demands. One student responded: “They are basic and [the strikers are] asking for simple decency. The payment situation is appalling.” Another wrote: “I pay over £9k and I think it’s disgusting how little of that money actually goes to them – they should be paid what they are worth.” The discrepancy between increasing revenue of universities and stagnant wages for academics was another major point that was raised.

"The interests of academic staff are not mutually exclusive to that of students"

As part of the investigation, we also reached out to a number of student societies that had made statements on the strikes.

Warwick Liberal Democrats told us that whilst they “lament on the impact of students”, they noted that “the university also has a responsibility on causing disruption to students” through a lack of effectively negotiating with Warwick UCU.

Image: Warwick Labour

Image: Warwick Labour

Warwick Pride, who organised the ‘Queer Liberation demands Queer Action’ teach-out highlighted the importance of “[raising] awareness of the economic inequality, job insecurity and stigmatisation of LGBTQUIA+ individuals” in reference to Warwick UCU’s intersectional approach to pay inequality. They also commented that “it’s important that Warwick Pride recognises the importance of people power, which the UCU represents”.

Perhaps the most vocal student supporters of the strikes, Warwick Marxists commented: “The interests of academic staff are not mutually exclusive to that of students.” They also mentioned that “in a sector that is highly overworked, underpaid and casualised, this has taken a toll on several academics’ physical and mental health” and that students’ education has been “directly compromised as a consequence of the marketised education system.”

"After two years of reduced contact hours and poor-quality online learning, this strike feels like a real kick in the teeth"

However, students’ opinions on the strikes were by no means homogeneous. Several respondents specifically mentioned the detrimental impact of the strikes on their education, particularly following the Covid-19 pandemic. One student responded: “After two years of reduced contact hours and poor-quality online learning, this strike feels like a real kick in the teeth.” Others were sympathetic to the demands of the strikers but did not think their actions would be effective in achieving their demands: “It feels a little like the only people it has an impact on are the students who missed their lectures. Then again, I am unsure what else can be done”.

Warwick Conservative Association told us: “Students pay exorbitant fees and rightly expect to receive a world-class education in return. Too often their interests are left by the wayside”. They added: “We support the right of UCU members to seek better compensation but holding students’ education hostage is not the way to do so.”

Overall, 71.4% of students surveyed responded that they supported the UCU strikes with many noting that they saw industrial action as a last resort for an ill-treated staff. While most students agree with the demands of strikers, many feel like their interests have been ignored in the discussion. A sizeable number (19.0%) of respondents stated that they believed the strikers’ demands were reasonable yet did not support the strikes.

Our investigation has shown that industrial action in higher education cannot be seen as a simple dispute between university administrations and staff: it is important that the impact on education and the needs of students, who have already suffered through Covid lockdowns and the cost-of-living crisis, must also be considered.

Image: secretlondon123 / Flickr

Image: secretlondon123 / Flickr